On Sunday, February 21, 1932, Rev. Dr. Wendell Holmes McRidley — 91 years old, a former slave-turned-educator and man of faith — was preparing his evening message inside the safe walls of the Cadiz Second Baptist Church.

He had already preached that morning, and it’s a place he and his wife, Annie, had called home together for more than 40 years — he having first answered those initial summons in 1881, and she wedding him August 12, 1887.

It’s a sermon, however, he didn’t get to deliver.

Creator of the Cadiz Normal and Theological Institute, a twice reserve delegate for the Republican National Convention, and founder/publisher/columnist of the nationally-acclaimed Baptist newspaper The Cadiz Informer, he died on the premises.

Born November 23, 1864, in Owensboro, she died 11 years later, on August 16, 1943, in Cadiz, where she had resided for 56 years.

Together, they are buried in the Cadiz United Brotherhood Federation Cemetery just off of Line and Depot streets, and still in unmarked graves. It is believed they lie in rest off a beaten path, far in the back along the tree line, but even that it is uncertain.

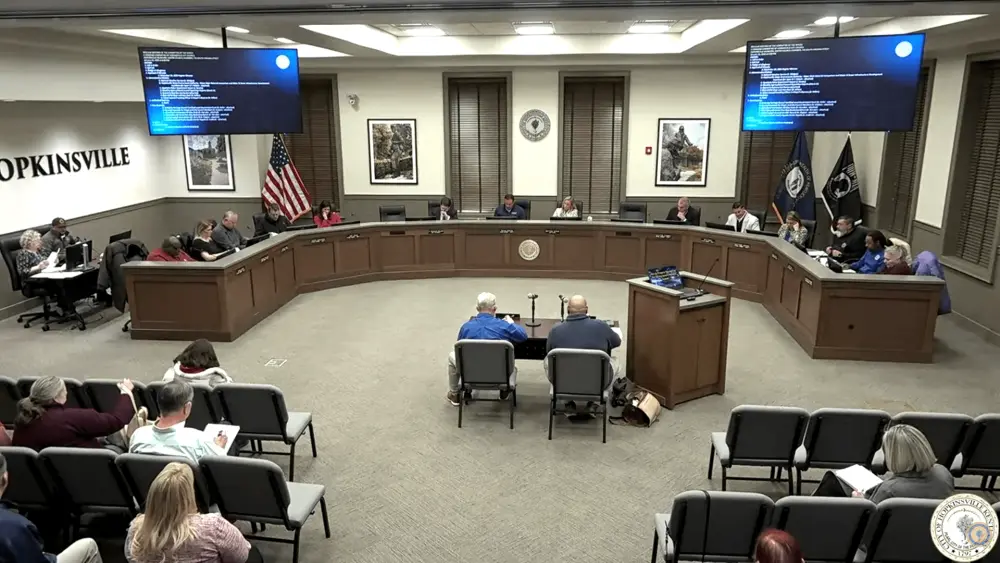

No longer in question, however, is their imprint on Trigg County’s history — made permanent Saturday when a large gathering observed the unveiling of a Kentucky Historical Society marker near their resting places, detailing their life’s accomplishments.

Several people are responsible for the sign’s installation — including the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet, the Kentucky General Assembly, local leaders and several curious researchers — but it’s Calandra Watts, and the Kiburi Circle History Club, who spearheaded the most critical efforts to preserve and present this memory.

In a full circle moment, Second Baptist Church Deacon and Genesis Express Historian Jonathan White offered invocation.

Jim Seaver, community engagement coordinator for the Kentucky Historical Society, spent time after the ceremony scouring the grounds — but during it noted the Commonwealth’s Historical Marker program allows for moments like this.

Cadiz Mayor Todd King presented Watts, and essentially the club, with a Key to the City.

Tanya Campbell-Boyd, a Trigg County native and Second Baptist Church member, said she grew up always hearing of Dr. McRidley from her great grandmother and aunties — and she knew about the school he created all those years ago.

Trigg County Judge-Executive Stan Humphries said he found it remarkable for a man to come from a slave plantation in Robertson County, Tennessee, all the way to west Kentucky for a lifetime of success.

Before the sign was revealed, Watts asked for youths Chandler Mayes and Jamariah Burks, not yet teenagers, to lay flowers at its base.

Mayes’ great-grandfather was John Tandy Alexander, who was educated at the Normal School founded by Rev. McRidley, and later served as a deacon.

Burks’ great-great maternal grandmother was Robbie Mayes, who was a member of Second Baptist Church during Rev. McRidley’s pastorship.

A Second Baptist History

An article penned by Mrs. Shirley Cunningham for the May 4, 1967, edition of The Cadiz Record details a remarkable history for the Second Baptist Church — one in which the McRidley’s played a critical role.

On May 13, 1842, nearly two decades before The Civil War, African-Americans belonging to the Baptist denomination living in, and around, Cadiz reportedly met in the home of C.A. Jackson, for the purpose of organizing a separate church.

Examined, and then orthodoxed, they adopted a declaration of faith and church covenant, and were constituted under the name “Cadiz Y. United Baptist Church,” and began meeting in the court house. Of the 49 original parishioners, 26 were White, and 23 were black.

On September 25, 1870, 40 African-Americans asked for church letters, in order to form a separate congregation, and it’s this split that created the first iteration of the Second Baptist Church under Rev. R.D. Morehead, Rev. John F. White and Rev. Patterson.

White would only preach for a short time before Rev. William Waddell was called, and brought with him another 250 members.

A Rev. Chatman and Rev. Ross Carr followed when, in 1881, the McRidley’s were called, and remained for the next 51 years.

Lost History

One of the more difficult parts of the McRidley story is the loss of The Cadiz Informer.

A four-page, six-column newspaper, it was 26 inches wide and at its height cost $1.50 and held a circulation near 11,000.

Full of sociological and political editorials written by him, and others, the office burned July 18, 1931, in what the Baltimore Afro-American reported came from a lightning strike of a nearby tree. The office carried no insurance, but officials were in the middle of a 400-pound shipment of its old type. More than 2,000 books, including McRidley’s library, were destroyed.

Furthermore, Saturday’s posthumous honor actually brings a major concern into the forefront of Trigg County’s history.

The McRidley plots are only two of perhaps dozens, if not hundreds, of unmarked graves not only in UBF Cemetery, but in the city’s East End Cemetery — as well as a handful of other locations across the community.

And not all of the lost are African-American.

Other resources:

W.H. McRidley — a man of vision | Baptist-life | kentuckytoday.com

Full Audio From Saturday: